Over the next few weeks I’ll be crossposting pieces of the Fandom Then/Now webproject here. I’ll be moving in order through the site, starting with information about the project and ending with some of my ongoing questions. I’ll link back to the site in each post. Please consider commenting here using the #fandomthennow tag or on the site to share your thoughts and ideas. First up! Fan engagement and reading habits from 2008 and today…

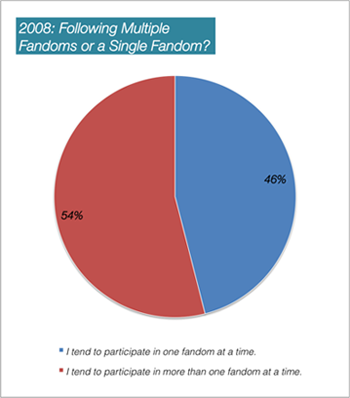

The image above shows the number of survey participants who were participating in a single fandom or multiple fandoms in 2008.

In the past, stories were often distributed within a fandom for a show, a pairing, a character, actor, etc. For example, stories could be shared on a fandom list-serv, in an online community dedicated to a specific pairing, posted on a dedicated fandom archive, etc. However, as media fandom increasingly used LiveJournal, this may have facilitated more long-term social links between fans across a variety of fandoms. In 2008, survey participants were almost evenly split between fans that engaged with more than one fandom at a time (54%) and fans who stuck to one fandom at a time (46%).

Today, I’m not sure what the trend is. With more media fans spread across sites like Archive of Our Own, FanFiction.net, Tumblr, and Twitter, LiveJournal, Dreamwidth, etc., I wonder if this is something that is enabling any different or new reading habits. Finding stories about a particular character or a certain pairing of characters doesn’t necessarily require joining one specific journal community or mailing-list any more. Instead, sites like Archive of Our Own, FanFiction.net, Tumblr, and Twitter allow fans to access many different fandom tags within a single website. This makes me wonder. Is it possible fans are reading a broader mix of fan fiction today? Are fans able to be more “multi-fannish” than they used to be?

Read the full write up on fan engagement here. Share what you think about this on the Fandom Then/Now website or respond here using the #fandomthennow tag.

Tag: fan fiction

Over the next few weeks I’ll be crossposting pieces of the Fandom Then/Now webproject here. I’ll be moving in order through the site, starting with information about the project and ending with some of my ongoing questions. I’ll link back to the site in each post. Please consider commenting here using the #fandomthennow tag or on the site to share your thoughts and ideas. First up! Fan engagement and reading habits from 2008 and today…

The chart above shows the types of fan fiction represented on Archive of Our Own (AO3) as of December 2013. On AO3, m/m has nearly double the amount of stories that some of the other categories do. This indicates that there are a lot of people writing m/m on A03. However, it’s important to read these numbers carefully and in context. This doesn’t necessarily indicate that slash is more prevalent than other types of fan fiction. While AO3 is a popular archive, it isn’t representative of all available fan fiction. For example, in my 2008 survey, Jane Austen related fan fiction was one of the most popular fandoms. At the time, this fandom was totally new to me, simply because I’d been so focused on studying fans connected to LiveJournal. At the time, Austen fans had several fan fiction archives elsewhere, exclusively dedicated to Austen-related stories. Similarly, the Whovians are often found on A Teaspoon And An Open Mind. There are countless other fandom specific archives out there.

Another important factor shaping the current AO3 numbers may be the archive’s “adult content” policy. AO3 allows it, FanFiction.net did once but no longer does. While Fiction Alley has been a popular archive for Harry Potter fans, it doesn’t allow stories with adult content either. These kinds of content policies may lead fans with shared interests to cluster on particular websites, spending more or less time on AO3, depending on their reading preferences. Adult content restrictions may also disproportionately affect the amounts of m/m or f/f content represented on different web archives. With so many different sites collecting fan fiction and catering to different groups of writers and readers, it may not ever be possible to fully map the kinds of fan fiction read by fans.

What do you notice about your fan fiction reading habits? Do you find yourself preferring a certain website, community or archive more than others? Or, do you look reading material in many different places?

If you’ve been reading fan fiction for a while, how have the websites you visit changed over time?

Read the full write up on fan engagement here. Share what you think about this on the Fandom Then/Now website or respond here using the #fandomthennow tag.

Are you planning on redoing the survey at any point? I love what you have up, but I think it would be fascinating to see more quantifiable information about how things have changed.

I think that’s a really great question/problem to tackle. WIth fans so dispersed across different sites these days. I actually wonder if we could do this with any validity today. I got about 7700 participants and the survey was shared on multiple websites and fan communities beyond LiveJournal. Nonetheless, I still don’t know if the original ‘08 survey would have worked or have gotten the response rate it did if so many fans hadn’t been connected on LiveJournal at the time.

Have you seen Centrumlumina’s AO3 Census? That’s the most recent analysis I’ve seen with a really significant number of participants. They report getting 10,005 survey responses. I’m not entirely clear what their recruiting method was (the write ups on Tumblr don’t seem to say) but the limitations post seems to imply it was promoted heavily on Tumblr.

Overall, each of these surveys can probably only be said to speak to a particular body of survey participants. Given the websites being used, it’s also probably a particularly Western/American and English language speaking body of fans. (I’ve got some geographic data from my ‘08 survey that reinforces this re. my survey. I’m just speculating that it would be similar with Centrumlumina’s research.)

Ultimately, my work is much more qualitative than quantitative so I’m not sure I’d be the best person to do it either way. However, I think it’s a fascinating question/problem to wrestle with. How would we do this today? I suspect many of us would turn to AO3 for numbers (I’ve already seen academics doing this at conferences). And, it would certainly be possible to do repeated check-ins on AO3 every 5-10 years to see changes in popular fandoms etc.

I wonder about that the implications of that though… AO3 represents a particularly long-lived and robust network of fan activity. (One very intertwined with the Transformative Works and Cultures organization.) It’s just one node of activity though. The question that always nags at me is: Are we repeatedly conflating one particularly visible portion of fans with all fans? I’m not sure there’s a clear way of resolving this problem, but it is part of the reason I’m so interested in getting different fan’s reactions to projects like mine. I’m always looking to see what other experiences might be out there.

(I had a similar experience reading Sheenagh Pugh’s Fanfiction: The Democratic Genre in 2007. It’s particularly focused on the UK and I remember being confused and fascinated by how certain fandoms were represented by Pugh. The picture it painted of certain fandoms just didn’t represent what I was noticing. However, it also made me aware of fandoms that I didn’t realize were around and active.)

Actually, I’m about to post something moderately connected to all of this. I did take a look at the current numbers on AO3 to see what they looked like in relation to the numbers I got in ‘08, but this also raised a lot of questions for me. If you’re interested, keep an eye on this space. I’ll be posting it in a few minutes. :)

About the Project

Over the next few weeks I’ll be crossposting pieces of the Fandom Then/Now webproject here. I’ll be moving in order through the site, starting with information about the project and ending with some of my ongoing questions. I’ll link back to the site in each post. Please consider commenting here or on the site to share your thoughts and ideas. But, before we begin, let me introduce myself.

About the Project

Fandom Then/Now is an idea I’ve been sitting on for a while. When I completed my MA Thesis in 2008, I shared the final thesis project with individuals who asked to see it. However, I’d done a large survey as part of the thesis project and I really wanted to share the results with fans. At the time, I got the idea to put all my results online and open them up for fans to look at and give input on. I was getting ready to do start this in 2009 but then SurveyFail happened.

SurveyFail was incredibly unsettling to me. Roughly one year after I launched my 2008 project, here were these two individuals (Ogi Ogas and Sai Gaddam) calling their survey project the same exact name as my 2008 survey and using eerily similar methods to reach out to fans and request for fan participation. And yet, Ogas and Gaddam’s motives, politics, and research ethics seemed to be completely contrary to my own.

At the time in 2009, my response was to duck and hide. I didn’t want to give Ogas and Gaddam any publicity and I didn’t want any research I’d done associated with them. The SurveyFail incident also made me particularly concerned about the ways research on fans is conducted. I felt strongly that research on fans and digital cultures is a process that must have more dialogue built into it. In October 2010 I presented “Fen Responses to Fan Research: Methods of Participation and Engagement” at the Midwest Popular Culture/American Culture Association’s annual conference. In this paper I reflected on my 2008 survey project, the 2009 SurveyFail incident and called for fan researchers to design more participatory and conversational research projects. I hoped that this participatory approach would help to counterbalance some of the issues that internet/digital culture researchers were struggling with at the time.

Fandom Then/Now is an experiment. It’s my way of testing out what a participatory and ongoing research project might look like. As a scholar, I begin any new project by building on my past experiences and research. That’s where Fandom Then/Now begins. I’m starting with past work that has been integral to shaping my thoughts about fan fiction and romantic storytelling. Into this, I’ve woven in many of the questions and ideas that are driving my current research project (my dissertation).

I want to share these initial thoughts and ideas while I’m working on my dissertation. I’m hoping that fans will be able to add their own thoughts along the way and help to shape the research. My goal is for fans to participate not as research “subjects” or bits of data, but as peer reviewers.

About Me

I am Katherine Morrissey, a PhD Candidate in Media, Cinema and Digital Studies in the English Department at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. I also have a Master’s in Communication, Culture and Technology from Georgetown University. My research focuses on production networks for popular culture, representations of female desire, and the ways that digital production is reorganizing romantic storytelling. My research is grounded in my experiences as a queer feminist, geek girl, and acafan. I have been actively participating in fan communities since 1996.

At UWM, I’ve taught courses on film, television, and digital media, participatory culture, and romance genres across media. I will be starting a Visiting Assistant Professor position at the Rochester Institute of Technology in fall 2014. I also have professional experience in web and graphic design, as well as communications and marketing in the non-profit sector.

If you’d like to check out some of my other recent work, you might be interested in the following:

“Fan/dom: People, Practices, and Networks.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 14, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2013.0532.

“Fifty Shades of Remix: The Intersecting Pleasures of Commercial & Fan Romances.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies. 4.1. (2014) 1-17.

Announcing the Fandom Then/Now Webproject

For many people, fan fiction is as much a part of their reading as commercial literature. Fan fiction websites and archives provide readers with novels, serials, novellas, romantic and erotic stories, non-romantic stories, experimental literature, video and visual art, etc. While fan writers and readers are certainly not exclusively interested in romance, fan writing frequently explores the romantic potential between two characters and fan fiction is often built on romantic foundations. The shift to digital publishing and reading is having a dramatic impact on commercial romance literature. However, what about the kinds of romantic and erotic stories fans produce? How is fan work being affected by the rise in digital publishing? The Fandom Then/Now project is designed to facilitate fan conversations and collect ideas from fans about fan fiction’s past and future.

What do you notice in the data from 2008? What do you think about the intersections between fan fiction and romantic storytelling? Now, in 2014, what has and hasn’t changed about fans’ reading and writing practices?

Please visit the Fandom Then/Now website to look at the project and share your thoughts.

Please help me spread the word about this project. I’m also happy to answer questions if you want to send them my way.

The idea of fan cultures, or “fandoms,” cultivating fan fiction writers began at the earliest in the 1920s with societies dedicated to Jane Austen and Sherlock Holmes, but took off in the late 1960s with the advent of Star Trek fanzines. The negative stereotype of “fans today is that of obsessed geeks, like “Trekkies, who love nothing more than to watch the same installments over and over…” However, this represents a core misunderstanding of what it is to be a fan: that is, to have the “ability to transform personal reaction into social interaction, spectatorial culture into participatory culture… not by being a regular viewer of a particular program but by translating that viewing into some kind of cultural activity.” Henry Jenkins, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor and expert on fan culture, likens fan fiction to the story of The Velveteen Rabbit: that the investment in something is what gives it a meaning rather than any intrinsic merits or economic value. For fans who invest in a television show, book, or movie, that investment sparks production, and reading or viewing sparks writing, until the two are inseparable. They are not watching the same thing over and over, but rather are creating something new instead.

Casey Fiesler, Everything I Need To Know I Learned from Fandom: How Existing Social Norms Can Help Shape the Next Generation of User-Generated Content, p735

Update: Now with link to an open access version of the paper and correct page, apologies for the typo.

The idea of fan cultures, or “fandoms,” cultivating fan fiction writers began at the earliest in the 1920s with societies dedicated to Jane Austen and Sherlock Holmes, but took off in the late 1960s with the advent of Star Trek fanzines. The negative stereotype of “fans today is that of obsessed geeks, like “Trekkies, who love nothing more than to watch the same installments over and over…” However, this represents a core misunderstanding of what it is to be a fan: that is, to have the “ability to transform personal reaction into social interaction, spectatorial culture into participatory culture… not by being a regular viewer of a particular program but by translating that viewing into some kind of cultural activity.” Henry Jenkins, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor and expert on fan culture, likens fan fiction to the story of The Velveteen Rabbit: that the investment in something is what gives it a meaning rather than any intrinsic merits or economic value. For fans who invest in a television show, book, or movie, that investment sparks production, and reading or viewing sparks writing, until the two are inseparable. They are not watching the same thing over and over, but rather are creating something new instead.

Casey Fiesler, Everything I Need To Know I Learned from Fandom: How Existing Social Norms Can Help Shape the Next Generation of User-Generated Content, p735

Update: Now with link to an open access version of the paper and correct page, apologies for the typo.

So if being online is so important to fanfiction, why has Amazon not adopted this central mechanism which could have drawn millions of views to its own online site? One reason may simply be that they are relying on sites like Wattpad to generate the traffic to Kindle Worlds. The other may have to do with content control. The plural “Worlds” in Kindle Worlds marks a clear separation between the different fanbases; there will be no boundary crossing here. For fanfiction, boundary crossing of various types is the point. Trying to constrain the unconstrainable is an inherent paradox in a model based on content control. Of course, one way to attempt to control content/text is to contain it in a book rather than have it online where control is always subject to slippage. However, the existence of Fanfiction itself undermines this attempt. Amazon and the licensors have a difficult balancing act. Most licensors would want to retain control over the content that appears online and therefore restrict official content, whether it be original or fan-generated, to their own fan sites; it might indeed be very difficult to keep the licensed Worlds separate in one online environment.

So one could argue that the “form” of the ebook in this case, where online would normally be the “native” medium, answers primarily the needs of the licensors rather than those of the fans and readers. This is not to say that Kindle Worlds shouldn’t have ebooks; even in the fanfiction communities, people create ebooks of fanfics for free download. It is the fact that Kindle Worlds appears to be only about ebooks that is the issue in the context of fanfiction.

So if being online is so important to fanfiction, why has Amazon not adopted this central mechanism which could have drawn millions of views to its own online site? One reason may simply be that they are relying on sites like Wattpad to generate the traffic to Kindle Worlds. The other may have to do with content control. The plural “Worlds” in Kindle Worlds marks a clear separation between the different fanbases; there will be no boundary crossing here. For fanfiction, boundary crossing of various types is the point. Trying to constrain the unconstrainable is an inherent paradox in a model based on content control. Of course, one way to attempt to control content/text is to contain it in a book rather than have it online where control is always subject to slippage. However, the existence of Fanfiction itself undermines this attempt. Amazon and the licensors have a difficult balancing act. Most licensors would want to retain control over the content that appears online and therefore restrict official content, whether it be original or fan-generated, to their own fan sites; it might indeed be very difficult to keep the licensed Worlds separate in one online environment.

So one could argue that the “form” of the ebook in this case, where online would normally be the “native” medium, answers primarily the needs of the licensors rather than those of the fans and readers. This is not to say that Kindle Worlds shouldn’t have ebooks; even in the fanfiction communities, people create ebooks of fanfics for free download. It is the fact that Kindle Worlds appears to be only about ebooks that is the issue in the context of fanfiction.

Anna von Veh, Kindle Worlds: Bringing Fanfiction Into Line But Not Online?

The inseparability of sex and gender in practice is one of the things that romance genres make obsessively visible, and one of the ways in which romance is itself pornographic. Romance is always seeking to display the imperative bind between sex and gender without, perhaps, naming it as such. The imperative to visibility in porn is also embedded in the themes of revelation and discovery that shape a romance narrative, always exposing the truth of feelings, desires, and character, and always manipulating the audience’s desire to know what they already know… both romance and porn consume the question of sexed and gendered relationships more for its epistemological context than its content.

Catherine Driscoll (“One True Pairing,” 94)